Working with Dinosaurs - A question and answer session with Prof. Phil Manning.

We're delighted that Prof. Phil Manning is able to share his views on Natural History and education with us and has offered to answer some questions posed by teachers received via our recollective panel.

Prof. Phil Manning is Chair of Natural History and Director of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Ancient Life at the University of Manchester (UK). Phil has been elected a Fellow of the Explorers Club (New York), he is a Fellow of the Geological Society (London) and is also a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

Q. Why do you think it’s important for young people to study Natural History?

Natural History is all around us, but more importantly… we are part of this natural world. The disconnect between us and nature has grown, especially in the past few decades. If we are to solve the many challenges that face our planet today; it is critical that young people are able to gain a firm grasp of the language, issues and solutions that will empower them to implement the changes required to sustain the natural world.

Q. What understanding and skills do students need if they want to study NH at university?

Observation is possibly one of the most underrated skills. The ability to simply record what you see and map changes to the world in which we live. This is a key life skill that many adults have forgotten how to do. Sometimes the answers to the most complex questions are simply staring us right in the face and all we need do is simply state what we see, but then act on that observation.

A student who wishes to study natural history, should just do that and not be hampered by an immediate need for understanding and/or skills, as this will grow as they learn to observe and better interface with the natural world. If there ever was a topic that should be universally studied, especially given our intrinsic relationship with the said topic, it would be this discipline as it makes an excellent feeder for almost any subject at University.

Q. How would a Natural History GCSE enable progression to a relevant Degree with signposted employment opportunities?

First and foremost, a Natural History GCSE would make each and every student a better and more informed citizen on the natural world. An awareness of the world in which we live would yield vast benefits across all multiple disciplines at all levels, including at degree and postgraduate levels (whether it be the science of the arts). There is a growing need for environmentally sustainable solutions to the way humans interface with the natural world and this will be a major driver for the future green economy.

In the coming decade vast numbers of jobs will be impacted by the natural world, as commerce and industry realign with more sustainable approaches to the global economy. The bare minimum qualification that will help an individual navigate this new and evolving landscape would be the GCSE in Natural History.

Q. How has the research you have undertaken influenced industry?

There are multiple aspects of my research that have had an impact on industry, which is quite surprising when you consider that I spend much of my time studying extinct life!

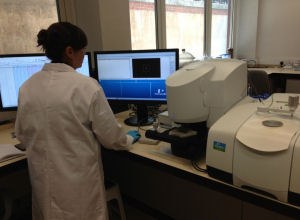

A purely economic impact results from the fact that our creative use of infrared imaging has inspired sales and product development for UK-based manufacturers of FTIR instruments as researchers in other sectors become aware of what modern instruments can achieve.

A purely economic impact results from the fact that our creative use of infrared imaging has inspired sales and product development for UK-based manufacturers of FTIR instruments as researchers in other sectors become aware of what modern instruments can achieve.

A second impact grows from the fact that our research has improved our predictive capability in geochemical systems that involve chemical immobilization and organic compound degradation, basically what happens when you bury something in the ground. Such systems include land based radioactive waste disposal and hydrocarbon exploitation.

Fossils provide the perfect experimental model of what happens to something when it is buried for thousands, millions or even billions of years… providing powerful hindsight to understanding the long-term safe storage of waste in a future world.

My third industrial example is made clear through the support of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), in that the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource has modified the facility development specifically to optimise the rapid scanning technology that my team and I have pioneered in collaboration with our project partners at Stanford. These developments will have sustained impact on users from multiple disciplines seeking to apply synchrotron-based elemental imaging.

The work that began with a group of scientists studying fossils and the preservation of biomaterials through deep time, has led to advances in the sensitivity and detection limits of our experimental techniques. It is these improved techniques that now permit the mapping of dilute traces of transition metals in human tissue (including brains) so that we might better understand the impact of environmental pollutants on our own health.

I would love to tell you the story of how my dinosaur research has helped NASA make space a safer place for astronauts, but that is very long story that involves intense x-rays and very large scanners…maybe next time!

Q. For students graduating with a NH degree what employment fields do they go into?

While I am employed by the University of Manchester as a Professor in Natural History, there is currently no single honours degree in this subject….but I think this will change!

I would hope that in the future a degree pathway might be developed under this umbrella, but at the moment there are related degree programmes that would allow graduates with a degree in the Earth, Environmental and/or Atmospheric sciences to explore a world of opportunities in the developing green economy that is so pivotal to our planet’s future.

Our graduates’ jobs include Scientific Research, Finance, Policy, blue-chip Management, Environmental Consultancy and Earth Resources. There has already been a major shift for many universities to offer a degree in Natural Sciences…it will only be a matter of time before a degree in Natural History is offered.

A key advantage that our graduates have over other science graduates is the experience gained during taught and independent fieldwork, which underpins our undergraduate teaching. Students develop multidisciplinary problem-solving and team-working skills during these trips, leading up to independent field-based projects in their third year of study, which provides students with precisely the experience and skills that graduate employers are looking for.

Q. With the recent move towards using DNA barcoding more widely to identify species from many groups, how do you think taxonomic skills (which many employers feel is sadly lacking amongst both undergraduates & graduates) can be promoted as a valuable tool for the next generation of Biologists?

There was a shift several decades ago from the macro to micro in biology. I have often heard students say that they are studying Darwin’s endless forms most beautiful, but down a microscope!

There was a shift several decades ago from the macro to micro in biology. I have often heard students say that they are studying Darwin’s endless forms most beautiful, but down a microscope!

My team has also helped develop and use proteomics (by extracting collagen sequences) to map the evolutionary relationships of long extinct lineages at a fraction of the cost of DNA barcoding. However, the ability to identify a species from their exo and endo-skeletons is also hugely important, especially as there are so many species still to be described on Earth.

It would be fair to argue that we are losing species more quickly than we can describe them, so the growth of basic taxonomic skills is pivotal to addressing this situation. My team and I have been working on sub-fossil bones in caves on the Cayman Islands (I hear you all weep for me!) and we needed both molecular and more traditional taxonomic skills to complete the study successfully, so both the old and the new can complement each other.

Q. How can the pandemic and the resulting lockdown change our ongoing relationship with the natural world?

I recall the first week of lockdown. The silence was almost deafening, but birdsong soon filled this sensory niche, as did so many sounds, sites and smells that many had forgotten. Even if it was short-lived, it seemed we had started to make a connection with the other species with whom we share this planet. It was possibly the first time for many to reconnect with the natural world in a way that was both uplifting and healing. There may still be some good to come from this devastating pandemic…staring with a broader appreciation of the natural world and how it plays such an important role in our well-being.

Q. What was the spark/hook that started you out in your career?

As a child my family moved from the outskirts of London to rural Somerset. After arriving in this ‘new world’ I decided that I would explore. The village where I lived was a natural history wonderland where I explored the past through the many fossils that littered my garden, but also the present through slowly learning the names of all the species of moth, butterfly, bird or critter that crossed my path. I am still learning today. The sense of wonder that I felt when I found my first fossil has never left me and I still feel this way today whenever I am exploring the Earth’s evolutionary past.

Q. What is your most favourite discovery and why?

Q. What is your most favourite discovery and why?

I discovered that by working in a team, I could achieve so much more. This has helped every facet of my career, both in the laboratory and in the field. It has also helped me appreciate that discovering something on your own is lonely, but to share it with others is exhilarating.

Q. How do you bring dinosaurs to life for your students?

64,000 volts and a tub of Flora usually does the trick! However, if the voltage and artificial spread are not available, the English language is wonderfully adept at crafting lost worlds and forgotten lives from duty old bones. The way in which we communicate science is critical to how it is perceived by audiences. Dry and cold words do not breathe life into old bones, but bright and creative metaphors can have a T. rex trip the light fantastic across the classroom.

Q. How can we carry forward the sustainability ethos, rather than it being just developed as a paper based qualification - it could advance further awareness of and responsibility for the natural world. Could it be an on-line qualification available to all or do you see other options?

All humans have to learn how to live sustainably if the Earth is to have a future in which we play a part. The planet has undergone multiple prior mass-extinctions events, one in particular (250 million years ago) saw the extinction of 95% of species on Earth. So, if our species wants to keep an evolutionary foothold on Earth, it is imperative that we learn how to live sustainably.

This ‘ethos’ must form part of our lives from the second we learn to explore the world in which we live. It should be reinforced throughout informal and formal education environments, but also into the workplace if we are to meet the many challenges that face our planet today.

Online learning would have the potential to permit many around the globe to share their own stories, experience and potential solutions to what might become a truly organic curriculum that adapts to the changing environments around the globe.

Q. Can you share your initial thoughts about setting up on-line teaching and learning modules that might help to ease the issues with students due to possible changes to teaching and learning stemming from the pandemic?

Online teaching has the great potential to reach new audiences and permit adaptive flexible learning, but it has to start with the basic premise that all must have access to technology that allows participation. If all potential students had access to online modules, the next step would be to make the content and delivery as engaging as possible.

Online teaching has the great potential to reach new audiences and permit adaptive flexible learning, but it has to start with the basic premise that all must have access to technology that allows participation. If all potential students had access to online modules, the next step would be to make the content and delivery as engaging as possible.

In all honesty I feel that a blended approach that includes face-to-face, online content and the tactile value of workshops and practical labs. For the teaching of natural history we are lucky that the lab is on our doorstep, once you step through your doorway to the outside world, there is the potential to engage with our environment in new and exciting ways. We need to find ways of making the technology support a more field-based approach to learning, but not forgetting to learn new ways to engage with nature.

Bio and background

Prof. Phil Manning is Chair of Natural History and Director of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Ancient Life at the University of Manchester (UK). Phil has been elected a Fellow of the Explorers Club (New York), he is a Fellow of the Geological Society (London) and is also a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

His research is both broad and interdisciplinary with active research projects including: Dinosaur biomechanics, taphonomy of soft tissue in the fossil record, the geochemistry and elemental analysis of fossils (particularly specialising in synchrotron-based imaging techniques), application of LiDAR-based imaging to both landscape and skeletal modelling (integrating stress-constrained multibody dynamics) and the mechanical analysis of biomaterials (both extant and extinct).

Prof. Manning and his team continue to undertake field-based research in the Hell Creek and Morrison Formations of South Dakota, Wyoming and Montana, but his fieldwork also includes sites in South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and the UK. In 2020 he was awarded the Sorby Medal by the Yorkshire Geological Society for his distinguished research contributions to the geosciences. Prof. Manning has written, presented and been co-producer on multiple television documentaries for National Geographic Channel, BBC, History Channel and multiple other networks from around the globe.

In 2015 he was a contributor to film documentary ‘Dinosaur 13’ that was awarded the Emmy for Outstanding Science and Technology Programming at the 36th Annual News and Documentary Emmy Awards held in New York. He continues to play an active role in public outreach for the University of Manchester, contributing to open-days, public lectures and workshops. He has authored books for children, also popular science books and is a regular contributor to public speaking events around the world, promoting the public engagement of science.

Check out Prof. Phil Manning's recent Royal Society talk: Extinction: Evolution's Partner in Crime?

Keep up to date with our proposed GCSE in Natural History and other Cambridge OCR Natural History news by signing up our email newsletter and updates. You can read back issues of our Natural History newsletter here.